by Justin Coile December 9, 2012

Abstract

Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE) has been gaining popularity in recent years due to federal incentives and demonstrated benefits. It still has yet to be implemented in the majority of hospitals in the United States. The high cost of implementation and uncertainty of the benefits among stakeholders are some reasons why this technology has not been more widely adopted. This paper discusses some of the user concerns with CPOE and looks into the impact on the workflow of various stakeholders. The benefits of decreased waiting, increased accuracy and reduced errors are also examined. The aim is to provide information to leadership to aid in a successful implementation of this emerging technology.

Introduction

Information technology has engrained itself into the modern healthcare system. The push to integrate technology into the delivery of care has intensified in recent years due in part to the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) passed in 2009 under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). This provided a financial incentive for providers and hospitals to adopt electronic health records and comply with meaningful use requirements. Computerized provider order entry (CPOE) is a major component of meaningful use and is being implemented by providers across the country. CPOE, when effectively used, has the potential to provide benefits to overall workflow and quality of care. Decreased waiting, increased accuracy and fewer errors are some of the benefits that can be realized in the streamlined ordering process. CPOE is a complex system and will have a substantial impact on the workflow of the health care team. There are many concerns amongst providers regarding the impact this system will have on their workflow. There are also questions about the potential benefits that CPOE could have for all of the stakeholders involved. Physicians, midlevel providers, nurses, pharmacists, unit secretaries, and patients are just some of the stakeholders that will be impacted by CPOE in some way. It is important to attain buy-in from all those involved to ensure a successful and meaningful adoption of CPOE. Implementing IT initiatives simply to meet “meaningful use” requirements will have very little meaningful impact for the organization. Initiatives like CPOE must be introduced in a culture that fosters innovation and change if the potential benefits are to be fully realized.

Methodology

A variety of methods were used to collect information for this report. First hand experience was gathered from time spent at a 206-bed freestanding academic cancer hospital, with active outpatient clinics and a research institute. This cancer center saw about 9,000 inpatient admissions and 328,000 outpatient visits in 2011. A literature review was conducted to assess the experiences of other health care providers when implementing CPOE and to gather some generalizable data.

Interviews with many of the stakeholders at the cancer center were conducted. Clinical based representatives included physicians, nurses, mid-level practitioners, pharmacists and unit secretaries. Representatives from risk management, performance improvement, process excellence and information technology were interviewed as well.

Observations were made in one of the inpatient units in the hospital. This was mainly to gather an understanding of the current process of order entry in the inpatient setting and clarify the roles of each member of the health care team. Observations were also done in the procedural setting, including endoscopy, pre-anesthesia testing, pre-op and the post anesthesia care unit. Time was spent with pharmacists in the main inpatient pharmacy to observe their process of medication order reception and verification, and to gather insight.

In order to learn from facilities that have already implemented CPOE the author reached out to other local hospitals. These hospitals included a local 1018-bed teaching hospital and a 259-bed children’s hospital.

User Concerns with CPOE

The implementation of CPOE in a hospital brings about a lot of change. Any change of this scope will be a cause of concern for the people it impacts, and the change to CPOE is certainly no exception. Much insight into staff concerns was gleaned through interviews and discussion with various stakeholders in the hospital. A review of the literature presents other areas of concern voiced by the end users.

CPOE will significantly impact physicians, so it is not surprising that they have already contemplated the potential downfalls. Physicians typically have a lot of work on their plate and are pulled in many different directions. Busy physicians sometimes struggle with human-computer interface issues, such as slow load times or freezes. These problems can be exacerbated when CPOE calls for a greater reliance on technology (Campbell, Guappone, Sittig, Dykstra, & Ash, 2009). The current computer issues faced by many physicians can contribute to a negative outlook for CPOE. To alleviate these concerns, the network infrastructure and end-user devices should receive adequate attention prior to the increased strain on the system that will occur with full CPOE implementation. Network connectivity must be assured everywhere in the hospital.

Another concern expressed by physicians is accessibility to a computer to input their orders. An extended login process adds to this concern. An adequate number of workstations for peak times need to be procured for all locations in the hospital. Updated technology such as single sign-on and remote desktops can be utilized to expedite login and reduce the overall time it takes to place orders.

Excessive interruptions with decision support features can cause alert fatigue, prompting them to ignore alerts that could be significant (Dixon & Zafar, 2009). Decision support functionality should be incrementally implemented to give prescribers time to adapt to the new features and prevent them from being overwhelmed by alerts.

Valid concerns have been expressed regarding CPOE’s impact on the provider-patient relationship. Time spent looking up documents in a patient’s medical record and entering orders into a computer can take away from time spent with the patient. Medical providers need to purposefully avoid too much computer time in order to talk with their patient and collaborate with the team who is caring for them. The provider will have to discover the most efficient workflow for them so they can accomplish all of these tasks. Ideally, entering an order into a CPOE system should not take any more of the provider’s time than writing it in a paper chart. Studies have found that productivity can drop about twenty percent in the first three months of CPOE implementation, but after users gain proficiency and develop a more efficient workflow productivity often improves (Campbell, Guappone, Sittig, Dykstra, & Ash, 2009).

One of the benefits of CPOE can also be a cause of concern for the care team. Because orders can be input from any location, communication between the members of the care team can be impacted. CPOE systems can contribute to a loss in “situation awareness”. An example of this was discussed in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, where a physician was examining his patient in the ICU when an order for dopamine showed up. This surprised the physician; the order was not there before, the patient didn’t seem to need the drug so he cancelled the order. As it turned out, the order was for a pre-op medication the anesthesiologist entered as he was preparing for his case the next day (Campbell, Guappone, Sittig, Dykstra, & Ash, 2009). A nurse on a hospital inpatient unit expressed this concern during an interview. She was worried that orders would be missed because the doctors would not tell the nursing staff when a new order was placed. A properly designed software system would alert nurses about orders that need to be addressed and this situation should not occur.

The streamlined process of order entry, discussed in the next section, can significantly decrease the workload requirements of some members of the health care team. This reduced workload can cause concern among the affected staff members about the security of their employment or a reduction in hours. While this is a valid concern for some, these employees may be utilized in other roles to improve patient outcomes. An example would be using pharmacists who spent much of their time verifying orders to round with physicians to aid in decision-making or ensure proper drug administration (Aarts, Ash, & Berg, 2007).

More information for researchers

When providers enter their orders using CPOE, they inadvertently create huge amounts of data. This data has always been produced, but when it is produced electronically it can be stored and organized into a format that can benefit researchers. Vanderbilt University Medical Center is one example where CPOE is used to aid in their clinical research. Data from orders entered electronically are stored and categorized in their electronic medical record. With Institutional Review Board approval, researchers can specify eligibility criteria for Informatics Center programmers. These programmers can create a secure website with a list of patients who meet the eligibility criteria for the study. (AAMC, 2002)

Vanderbilt has also used their IT system to track when patients receive their first doses of research specified medications. They can categorize patients based on admission diagnoses, reasons for certain tests and medications and other parameters or combinations of these. This has all made study enrollment far more efficient than by manual means. (AAMC, 2002)

The Impact on Workflow

One of the major reservations providers have with CPOE is the uncertainty of how this technology will impact their workflow (PR Newswire, 2012). The use of this technology will significantly change the way physicians currently place orders. It will take some time to adapt to the new workflow and for providers to develop a process that is most efficient for them. Both clinical workflow and the CPOE system can be modified over time to mitigate issues and create the most efficient workflow (Campbell, Guappone, Sittig, Dykstra, & Ash, 2009). Disadvantages identified in a 2009 study were possible time consuming and problematic user-system interactions (Niazkhani, Habibollah, Berg, & Aarts, 2009). This problem has existed for a long time, computers and humans don’t always get along and malfunctions can be very frustrating. With increased attention and funding given to computer systems in hospitals, many of the hardware and software errors experienced by healthcare professionals should be alleviated. Evidence of this can be seen in the rock-solid reliability of technology in the airline and banking industries.

Despite the concerns expressed by providers, one of the key benefits of CPOE is the way it restructures the workflow from order transcription through pharmacist verification. The current method of order input in many hospitals is a complex web of tasks that are completed by several people with varying roles. It is a mix of manual and automated processes, all of which have to occur flawlessly to ensure the intentions of the prescriber are fulfilled. Some of the roles overlap, creating indecision and confusion that can lead to orders being missed, delayed or misinterpreted. Another benefit to workflow is the ability for physicians to enter orders from locations other than the patient’s bedside, including their office at the hospital, the cafeteria and even their own home or the theater (Aarts, Ash, & Berg, 2007).

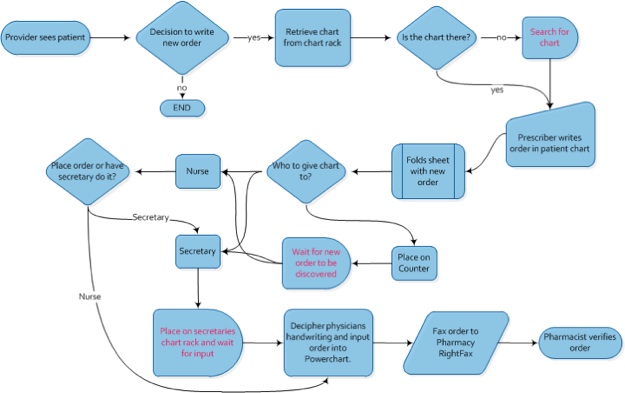

In the flowchart below you can see the complexities involved in the process of order entry that were observed on an inpatient unit in the cancer hospital. There are many steps and many hands involved in carrying out what should be a relatively simple task. After the provider sees the patient and decides to write an order they need to find the patient’s chart. On several occasions in a matter of a few hours providers were observed searching for the chart and enlisting help to locate it. While there is a chart rack designated to hold the patients chart, it is often not there because someone on the health care team is, will be or has been using it. Time spent searching for the chart is completely wasted and contributes to a delay in order fulfillment; these delays are denoted in the flowchart as red text. After the chart is located, the provider writes the order and folds the order sheet to signify that a new order has been written. Then the provider has to decide what to do with the chart. Sometimes a nurse or other member of the healthcare team is notified about the order and the chart is given to them. Other times the chart is placed in a chart rack on the unit secretary’s desk or just left on the counter. Once the order is discovered either the unit secretary or a nurse will decipher the order. Illegible handwriting is commonplace in many hospitals, and can contribute to errors or extra time spent clarifying the prescriber’s intention. Once the order is clearly deciphered it is entered into the computer system; medication orders are also faxed to the pharmacy for pharmacist verification. Significant delays were observed waiting for the newly written order to be discovered and waiting for the backlog of orders to be entered by the unit secretary. After medication orders are entered into the computer and faxed to the pharmacy, a pharmacist will verify them. If a discrepancy is found the pharmacist will either make the necessary corrections or contact another person on the health care team for clarification.

Before CPOE Deployment

After CPOE Deployment (Proposed)

The simplified and streamlined process after CPOE implementation can be seen in the flowchart directly above. In this process one person, the prescriber, is responsible for order transcription before the pharmacist receives the order. This person still collaborates with the healthcare team when deciding how to best treat the patient, but when it’s time to place an order they do it. When they do, the software has the ability to double check for potential issues, like allergic reactions or toxic doses, then the order is received in the pharmacy immediately after the prescriber electronically signs their order. There is no waiting for the secretary to fax the order or try and decipher the scribbled handwriting in the paper chart. There are also benefits to pharmacy workflow that could allow pharmacists to have more time to round with physicians and ensure proper drug administration (Aarts, Ash, & Berg, 2007).

The efficiencies gained in the improved workflow of CPOE have benefits greater than simply freeing up resources for increased productivity elsewhere. The streamlined workflow spurs benefits to effectiveness and quality of care, including decreased waiting, increased accuracy and fewer errors.

Decreased Waiting

One of the side effects of the improved workflow of CPOE is a reduction in the wait time experienced by a patient to receive treatment. The multiple steps of the current process and the delays between steps contribute to a delay in the patient receiving the care they need. A study at Denver Health Medical Center found that laboratory, radiology and pharmacy turnaround times fell dramatically with full implementation of CPOE. Laboratory turnaround times decreased from 142 to 65 minutes, a 54.5% reduction. Radiology went from 31 to 11.9 hours, a 61.5% reduction; and pharmacy decreased from 44 to 7.3 minutes, or 83.4% (Steele & Debrow, 2008).

A study to look specifically at the impact of CPOE on medication order processing time was conducted at Pitt County Memorial Hospital. This is a 761-bed tertiary care hospital in Greenville, North Carolina. This study focused on the time from order composition to pharmacist verification, unlike other studies that considered total medication turnaround time. The main impact of CPOE on medication order processing occurs from order composition to pharmacist verification, delivery and administration of medications are not significantly impacted by CPOE. It was found that the mean order processing time was reduced from 115 minutes to just 3, a 97% reduction. The average time it took from order composition to the time the order was sent to the pharmacy was 84 minutes. All of the steps involved with this process were eliminated in the streamlined workflow of CPOE and the pharmacist receives the order instantly. The time it took a pharmacist to verify orders entered with CPOE was also dramatically decreased by 90%, from a mean of 31 minutes to 3 (Wietholter, Sitterson, & Allison, 2009). The improvement in pharmacist efficiency is largely a result of the increased accuracy of orders entered through the CPOE system.

Increased Accuracy

The implementation of CPOE allows for an increase in accuracy, appropriateness and completeness of orders. This is accomplished through additional functionalities of the system including decision support and standardized order sets. These technologies help guide physicians to follow evidence-based practices.

CPOE implementation presents an ideal time for the standardization of care in a hospital. Individual specialty groups can collaborate to develop standardized order sets for common situations based on current evidence. These pre-written order sets simplify the ordering process and should help improve the workflow of the prescriber. They also help ensure the provider does not accidentally omit an order that would be beneficial to their patient. A review of the current literature shows strong evidence that systems like this make it more likely that appropriate treatments or therapies are ordered (Bright, et al., 2012).

Decision support systems (DSS) can be built into CPOE to assist prescribers in ordering the most appropriate treatment. These systems know the patient’s allergies, current medications, medical issues, height, weight, age and other pertinent information. New orders are automatically checked for duplicate orders, drug-drug interactions, potential allergic reactions and clinical appropriateness (Handler, et al., 2004). DSS can recommend prerequisite or subsequent tests and automatically calculate recommended dosage based on height, weight, age and physiology (Doolan & Bates, 2002). The system can also assist the provider in choosing the best medication based on insurer formulary information and recommend more cost effective alternatives for the patient (Handler, et al., 2004).

The issue of incomplete orders is also mitigated with the use of CPOE. Pre-written, complete order “sentences” allow for the provider to easily select the desired treatment, and can also help guide them to evidence based recommendations. These sentences include all the necessary information to fulfill the order such as route, dose, frequency, start time, duration and other parameters. The prescriber can still modify these fields to suit their needs, but the system should prevent orders being placed without all the necessary information.

Fewer Errors

Medical errors occur far too often in the healthcare industry and can have disastrous results. Well over half a million people are injured or killed in America’s hospitals every year due to adverse drug events (Shamliyan, Duval, Du, & Kane, 2008). A review of recent incidence reports at the cancer center reveals that many of these adverse drug events are the result of ordering and transcription errors that would have been prevented if CPOE were utilized. This is a serious problem with real, devastating consequences. A 1995 study found that 62% of preventable ADE’s occurred in the ordering or transcription phase (Bates, Cullin, & Laird, Incidence of Adverse Drug Events and Potential Adverse Drug Events: Implications for Prevention, 1995). Adverse drug events are also a costly occurrence averaging thousands of dollars each, with the nationwide costs in the billions (Bates, et al., 1999).

The impact of CPOE on reducing medication errors has been well documented. A literature review conducted by researchers at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health found that 80% of studies reported a significant reduction in total prescribing errors (Shamliyan, Duval, Du, & Kane, 2008). The simplification of the ordering process and the impacts previously discussed contribute to this reduction in errors. Each step in the flowcharted workflow is an opportunity for error and each person involved must perform flawlessly every time to prevent an error from occurring. The current process in use is not only inefficient, but also potentially dangerous.

A study was conducted at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, an academic teaching hospital in Boston affiliated with Harvard Medical School, to assess the impact that CPOE had on the reduction of medication errors. Medication errors were analyzed before CPOE implementation and in several periods after; each period with additional decision support functionality. The results were clear. There was a significant reduction in medication errors after initial implementation of CPOE, and further improvements resulted from added decision support features. There were large improvements in all main types of medication errors; dose, frequency, route, substitution and allergy. Non-missed-dose medication error rates fell from 142 per 1,000 patient days to 26.6, an 81% reduction. Non-intercepted serious medication errors, the type that cause injury, fell by 86%. (Bates, et al., 1999) This technology has the opportunity to positively impact the lives of so many people by making a hospital stay not such a dangerous affair.

Discussion

Implementing CPOE in a hospital is an enormous undertaking. A large investment both financially and in time is required to successfully bring this technology to the organization. With an increasing amount of hospitals implementing CPOE, it will soon be required if an organization is to remain competitive. While the recent incentives provided by the HITECH Act help offset a portion of the financial costs, the organizational change required by CPOE demands more than just money. Strong leadership with experience in change management will be needed. Senior leadership must ensure adequate resources are devoted to the effort. A popular Chief Medical Information Officer is crucial in gaining physician buy in. The stakeholders will have to embrace the technology for the full potential benefits to be realized.

Staff must be made aware of the reasons why this technology is being adopted. Change gets a much more positive reception when there is clear communication of the benefits it will bring to the organization, staff and patient. Stakeholder involvement in the implementation effort is key to ensuring the change is smooth for everyone. If the stakeholders truly understand and appreciate the positive impacts of CPOE they will embrace the change and everyone will benefit.

Bibliography

AAMC. (2002). Information Technology Enabling Clinical Research. Findings and

Recommendations from a Conference Sponsored by the Association of American Medical Colleges

with Funding from the National Science Foundation (pp. 34-36). Leesburg, VA: Association of

American Medical Colleges.

Aarts, J., Ash, J., & Berg, M. (2007). Extending the Understanding of Computerized Physician

Order Entry: Implications for Professional Collaboration, Workflow of Quality and Care.

International Journal of Medical Informatics , 76 (Supplement), S4-S13.

Bates, D. W., Cullin, D. J., & Laird, N. (1995). Incidence of Adverse Drug Events and Potential

Adverse Drug Events: Implications for Prevention. The Journal of the merican Medical Association ,

274, 29-34.

Bates, D. W., Leape, L. L., Cullen, D. J., Laird, N., Petersen, L. A., Teich, J. M., et al. (1998).

Effect of Computerized Physician Order Entry and a Team Intervention on Prevention of Serious

Medical Errors. Journal of the American Medical Association , 280 (12), 1311-1317.

Bates, D. W., Teich, J. M., Lee, J., Seger, D., Kuperman, G. J., Ma'Luf, N., et al. (1999). The

Impact of Computerized Physician Order Entry on Medication Error Prevention. Journal of the

American Medical Informatics Association , 6 (4), 313-321.

Bright, T. J., Wong, A., Dhurjati, R., Bristow, E., Bastian, L., Coeytaux, R. R., et al. (2012).

Effect of Clinical Decision-Support Systems. Annals of Internal Medicine , 157 (1), 29-43.

Campbell, E. M., Guappone, K. P., Sittig, D. F., Dykstra, R. H., & Ash, J. S. (2009).

Computerized Provider Order Entry Adoption: Implications for Clinical Workflow. Journal of

General Internal Medicine , 24 (1), 21-26.

Dixon, B. E., & Zafar, A. (2009). Inpatient Computerized Provider Order Entry (CPOE):

Findings from the AHRQ Health IT Portfolio. AHRQ Publication No. 09-0031-EF. Rockville, MD:

AHRQ National Resource Center for Health Information Technology.

Doolan, D. F., & Bates, D. W. (2002). Computerized Physician Order Entry Systems in

Hospitals: Mandates and Incentives. Health Affairs , 21 (4), 180-188.

Fear, F. (2011). Governance First, Technology Second to Effective CPOE Deployment. Health

Management Technology , 32 (8), 6-7.

Handler, J. A., Feied, C. F., Coonan, K., Vozenilek, J., Gillam, M., Peacock, P. R., et al. (2004).

Computerized Physician Order Entry and Online Decision Support. Academic Emergency Medicine ,

11 (11), 1135-1139.

Niazkhani, Z., Habibollah, P., Berg, M., & Aarts, J. (2009). The Impact of Computerized Order

Entry Systems on Inpatient Clinical Workflow: A Literature Review. Journal of the American Medical

Informatics Association , 16 (4), 539-549.

Ovretveit, J., Scott, T., Rundall, T. G., Shortell, S. M., & Brommels, M. (2007). Implementation

of Electronic Medical Records in Hospitals: Two Case Studies. Health Policy , 84, 181-190.

PR Newswire. (2012). Fifth Annual Healthcare IT Trends Survey Cites Resistance to

Workflow As Leading Obstacle to Cpoe Implementation. PR Newswire US.

Shamliyan, T. A., Duval, S., Du, J., & Kane, R. L. (2008). Just What the Doctor Ordered: Review

of the Evidence of the Impact of Computerized Physician Order Entry System on Medication Errors.

Health Services Research , 43 (1), 32-47.

Steele, A. M., & Debrow, M. (2008). Efficiency Gains with Computerized Provider Order

Entry. In K. Henriksen, J. B. Battles, M. A. Keyes, & M. L. Grady, Advances in Patient Safety: New

Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol. 4). Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Research and

Quality.

Wietholter, J., Sitterson, S., & Allison, S. (2009). Effects of computerized prescriber order

entry on pharmacy order-processing time. American Journal of Health-Sysytem Pharmacy , 66 (15),

1394-1398.

(c) 2012 Justin Coile

(c) 2012 Justin Coile